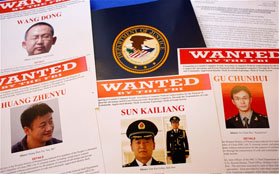

The United States recently indicted five Chinese military operatives for cyber espionage. The grand jury charges bring about 31 different counts that could result in sentencing the individuals to 227 years in prison combined (by my count). Many are calling the U.S. Justice Department’s latest move to punish Chinese citizens for cyber espionage an unprecedented step (a Google news search brings up an amusing number of articles that seem to basically copy each other). While this goes a bit too far in that the U.S. Government has punished individuals for state crimes before, this move to charge five Chinese military officials with espionage is clearly an escalatory step that also at the same time represents doing the least that can be done beyond doing nothing.

A strong reaction is likely. Jon Lindsay, notes that “it [the charges] does broach new ground by fingering Chinese military personnel actively serving in China. Retaliation by China, perhaps even outing US intelligence personnel serving at the NSA, is probably inevitable, although accusations are sure to be more rhetorical than evidence-based.”

In fact, China has taken the first step by calling the charges preposterous and charging the U.S. with double standards. They have called in the ambassador to launch a formal complaint and canceled cooperation on a cyber initiatives for the time being. Further action in private or in public is clearly forthcoming. China has also taken the step to ban Windows 8 on all government computers. A strong step in that Windows XP was so popular there and it was assumed that Windows 8 would be just as prevalent in the future. They are reacting both to these moves but also Microsoft’s abandonment of the XP operating system leaving current Chinese systems vulnerable.

All this does raise questions about the nature of the action and its context. While trying to restrain cyber espionage is a worthy goal, just when and where are we drawing the line and how? While economic espionage is supposed to be a bridge too far, Foreign Policy notes that it happens quite a bit, and sometimes by the U.S. government itself.

This leads us to ask why. Many people have given different reasons, such as a fundamental disagreement on the nature of the state. Adam Segal suggests is because the U.S. is frustrated. More concretely we have the issue of China trying to catch up to a vast power differential. The most likely reason though is a form of punishment that offers the path of least resistance. It is not just that the U.S. is frustrated, but that they want to do something, anything really, but taking a stronger stance will be met with more than rhetorical responses and calls for action.

My own take on the issue that this move is clearly represents a hardline stance taken by the United States. In the grand jury indictments, the United States is seeking to punish individuals responsible for crimes against the state organized by a state. At the same time, the U.S. is seeking to avoid punishing the state of China as a whole. This is the path of least resistance. The U.S. avoids blaming China directly for the sins of the individuals, but since they work for the Chinese military, there is little that can be done to distract any observer for noting that these were not rouge individuals.

While seemingly an easy step, it only invites escalation. Surely China will respond in a likewise manner further, as Lindsay suggested. Most problematic of all, China will likely not be receptive to moves for cyber norms of behavior that both states have called for. How can they take positive steps forward when the United States takes the first step, but in a negative direction? The Snowden revelations have only gone to prove that the United States has been hypocritical in their calls for cyber norms. Trying to misdirect attention away from their own misdeeds by calling attention to China’s violations only invites for the relationship between the two powers to remain on equal, but shaky foundations of continued espionage, misdirection, and subterfuge. In short, more of the same will result.

It will be interesting to see what the future holds. While all sides of the international debate on cyber security see the need for norms of behavior and global institutions to protect our digital foundations, the actual diplomatic practice between all sides remains the same. Each plays lip service to restricting cyber violations while at the same time continuing said violations. As has always been true negotiations, to stop the cycle someone needs to make concessions. Who will it be, if anyone?