One of the great gifts of teaching is that occasionally, you learn something. The opportunity to discuss things with students sometimes takes you down a path you didn’t expect and hadn’t seen before. The following emerged from a discussion with my Diplomacy & Negotiation class this week, and it’s a point wholly unexpected (to me, at least).

We were discussing third-party intervention into conflict: why countries intervene, how they justify intervention, when and under what circumstances interventions might be expected to be successful. In the course of the discussion, one student pointed out that there is a difference between intervening in internal conflicts (civil wars and the like) and intervening in a conflict between states. I started to talk about the relative decline of the latter and the increase in the former – an observation that is now largely background noise to those of us who study conflict – when it struck me that I hadn’t thought very much about why this was the case. And because we had earlier in the class been talking about the US as the system hegemon, an answer appeared largely unbidden: the post-WWII world was developed with almost exactly this outcome in mind. The rules of the current world system are designed to solve a particular problem; unfortunately, they are terrible for solving other kinds of problems.

This is probably not an original thought, and I’m sure someone else has published it already, but bear with me. The creation of the post-WWII world order, embodied among other things in the United Nations and its somewhat loose set of collective security rules, was designed to solve a particular challenge. That challenge was interstate wars that had a tendency to become massive, system-wide conflagrations – something that had happened twice in the space of forty years. Keeping this from happening again was, for everyone in 1945, the most important goal of a new international system.

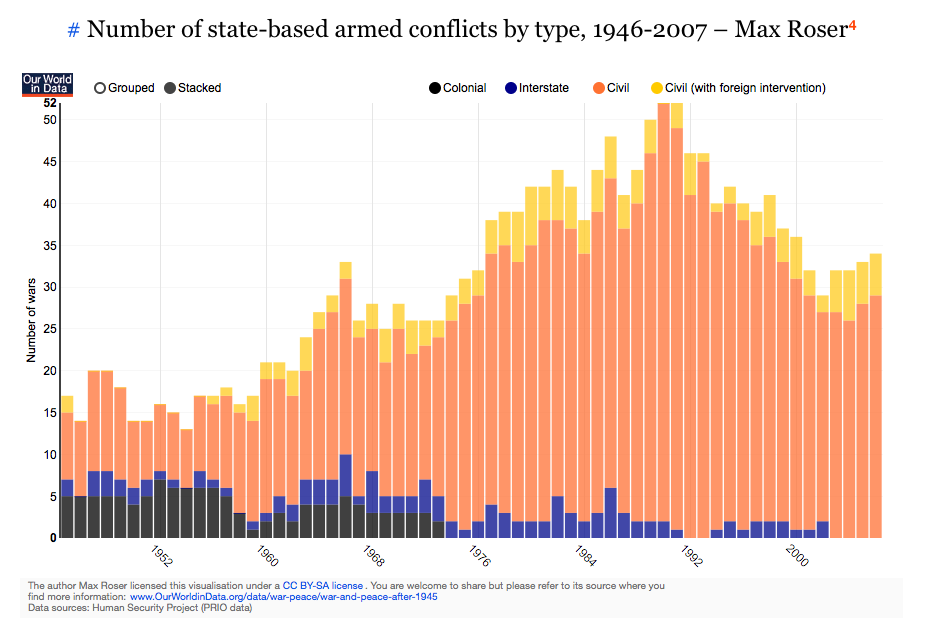

And as much as it is good sport to poke fun at the UN – its toothlessness, its inconsistencies, its tendency to enshrine the power of those who already have power – it and the world system of rules it represents have been remarkably effective at solving this one problem. Consider this graph, based on PRIO data of the number of wars in the world:

Interstate war (the blue bars) started fairly low (the graph starts at 1945) and dwindled from there, to the point that by the 21st century interstate war had all but died out. Yes, there have been a couple of notable exceptions – largely involving the United States – but on the whole, if you showed this graph (or the blue bars on it) to people in 1945 they would have been ecstatically happy.

The problem, of course, is the orange and yellow bars – the incidence of civil war. While these have come down from a peak around 1990, they’ve started to tick upwards again, and the overall incidence is FAR higher than it was when the current system was founded. Policymakers decry a world of civil conflicts – Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and now the Daesh/IS crisis – and wonder why the United States, currently the undisputed hegemon of the international system, can’t somehow bring order to this chaos. The answer is, we’ve never really tried.

The graph above is exactly what you would expect from a world system primarily set up to solve the problem of interstate wars. In so doing, that same system has taken away an outlet that in former eras was often used to deal with internal governance problems: go to war with your neighbor. With that avenue gone, states with internal governance problems either have to find a way to work out those problems peacefully, or do so violently. Many, obviously, have chosen the latter.

Our tendency is to think of the world in foreign policy, not international relations, terms. The foreign policy approach seeks to solve problems one at a time as they present themselves: what do we do about Libya? How can we solve the Syrian crisis? What’s the best way to deal with the Daesh movement and its claim of a new Caliphate? Of course, our track record on solving problems one at a time isn’t very good (not just recently but over the past 60+ years).

But foreign policy is made in the context of the international system – a system of rules and behaviors which we ourselves set up. We struggle to deal with civil wars and internal conflicts because we’re constrained by the rules of the sovereign state system, as Jay Ulfelder pointed out so well recently with regards to Yemen. So long as we live within the context of rules and structures designed to solve one problem, we are unlikely to have much success solving a wholly different problem.

Unfortunately, opportunities to rewrite the rules of the world only come along rarely – and then, usually after a massive crisis or systemic upheaval. I don’t think the United States can convene a global conference next week on reordering the world to deal with civil wars, even if there was interest in doing so. In some ways, the world of today is the result of the Devil’s Bargain we struck in morphing Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations (which, along with his 14 Points, tried very directly to deal with issues of internal governance) into the modern United Nations. We decided that solving internal political problems was too difficult – and maybe we were right – and so we punted and focused on the interstate stuff instead. The result is a world with a lot of civil war and very little interstate war.

I don’t know that there’s an obvious solution here. It would be interesting to see (and perhaps someone has already done) research on whether there is, in fact, an inverse relationship between interstate and intrastate war. It was also be interesting to see, as a thought experiment, what kinds of rules would need to be fashioned to make civil war as vanishingly rare as interstate war has become. Until then, however, I think we are stuck with a world where war is still pretty common – it’s just (mostly) contained within boxes of sovereign states.